By Thad Kelling, marketing and public relations manager, Lassonde Entrepreneur Institute

Cervical cancer is almost eradicated in the developed world, where detection is made quickly and treatments are readily available. But, in the developing world, where doctors and equipment are scarce, many more women die of the disease — as many as 90 percent of the 250,000 women who die of it annually.

A transdisciplinary team of U students hopes to solve this problem with a new, portable, handheld treatment device.

They started building the device with a $500 grant as part of the Bench-2-Bedside competition run by the U’s Center for Medical Innovation, the Lassonde Entrepreneur Institute and the College of Engineering. Now, they’re rapidly moving toward commercialization with a $15,000 first-place award from Bench-2-Bedside, vast support from industry experts, becoming the World Health Organization lead for cervical cancer and a new $2.4 million grant from the National Cancer Institute to study the device in Zambia.

“Relative to other cancers, cervical cancer stays precancerous for 10-20 years, but once it becomes cancer, it becomes very aggressive and few survive,” said Tim Pickett, one of the students on the team who graduated with a master’s in bioengineering in May 2015. “Because of the grace period, it’s basically curable in the developed world.”

Others on the team include Ashley Langell and Ashley Trane, medical students; Jennwood Chen and Sarah Lombardo, surgical residents; Brian Charlesworth, multidisciplinary design student; and Kris Loken, MBA and bioengineering graduate.

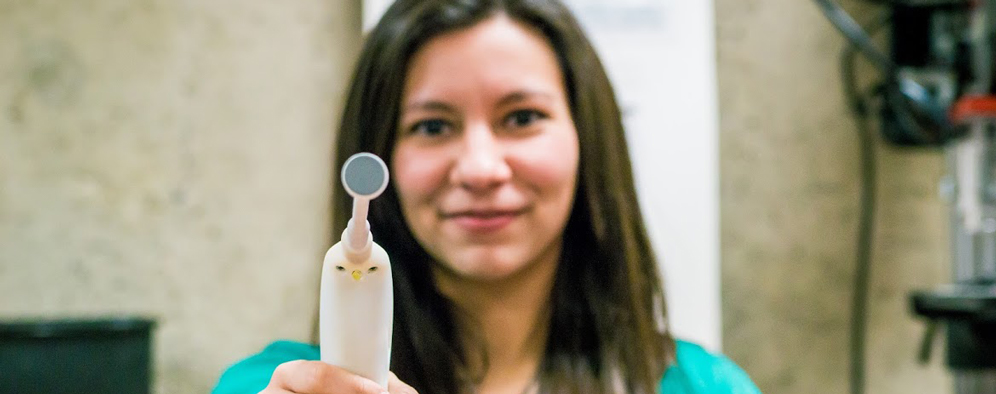

Their device, called Cinluma, looks like an ordinary battery-powered drill with a heating element on the end. It applies heat to the cervix and in just 45 seconds, through the process of thermocoagulation, eliminates lesions before they can become cancer. Unlike other treatments on the market, their device is inexpensive, reusable and battery-powered, so doctors don’t need a stable source of electricity.

“The probe just heats up to 100 degrees Celsius, or whatever temperature settings we program it for, and holds for 45 seconds,” Pickett said. “It’s a really simple device. It’s just a small heating element. Forty-five seconds can save your live.”

Team mentors include John Langell, a surgeon and director of the Center for Medical Innovation, and Dean Wallace, a doctor and entrepreneur who first identified the need to find a better treatment for cervical cancer in developing countries.

“We see our transdisciplinary student teams doing remarkable things in all of our medical innovation programs, including our Bench-2-Bedside competition,” Langell said. “The University of Utah is a global leader in medical innovation, and we are proud to carry on this tradition. Faculty and students are contributing in big ways. What is most impressive is the foundation for technology acceleration we have created at the U. Through resources like the Crocker Innovation and Design Lab, where this device was conceived and created. We took this technology from concept to full FDA filing in just seven months, something unheard of even at the largest international medical technology companies. ”

The Cinluma device is now managed by Wallace’s company, Cure Medical, where they have deep industry knowledge and technical skills to guide the development and regulatory process. However, the students continue to contribute.

The company has many developments underway. It filed for a U.S. patent on the device’s portability. It is working on the same protection in the European Union. Clinical studies will start soon at the U. And it has requested permission to sell the device from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

While the device is moving rapidly into the hands that need it, and the students look forward to helping save countless lives, they also appreciate the learning opportunity all of this has given them.

“It has been amazing to be part of an interdisciplinary team working on a prototype and device that may someday be used across the world,” Langell said. “As a medical student, I’m only starting my career, so I hope to be a part of many efforts like this one.”